Book review: Parfit

The tragedy of a genius who ended up focusing on what didn’t matter

David Edmonds' Parfit: A philosopher and his mission to save morality left unanswered the main question I had about the life of Derek Parfit: How does someone become so thoroughly obsessed with ethics? Not obsessed in the way a normal academic is captivated by their discipline, but something much deeper. I mean total consumption; a haunting feeling that if you don’t solve certain problems then everything else is meaningless.

This obsession resulted in someone who would only drink instant coffee because anything else takes too much time.Someone who would eat only simple foods that didn't require preparation—like apples and carrots—so that he didn't waste his time cooking. He exercised on a stationary bike so that he could read philosophy. His only question when meeting someone new was: What is your book about? In the last decade of his life he all but refused to socialize, moving to a house in the countryside so that he could work in peace. Meetings with students, when they happened, would famously last anywhere from four to 18 hours as he investigated their ideas with the ferocity of someone who thought those ideas had to save the world.

I read Parfit with the goal of understanding how such a mind works, how it develops. What motivates someone to dedicate so much of their waking life to ethics? How does someone become so possessed by the questions of moral philosophy?

Parfit, not for lack of trying, is unable to fully grapple with this question. I don’t view this as the fault of the book—I don't think a biographer could do a better job than Edmonds. Parfit's life was a mystery that he kept well hidden. There's only so much a biographer can do.

In fact, the biography makes the mystery of Parfit's obsession even more poignant. Edmonds highlights that he was not always so monomaniacally focused on ethics. In fact, his younger days were marked by a dazzling array of interests. At Eton (a boys only boarding school in the UK), he played the piano and the trumpet and participated in orchestra competitions. He was the president of the debate society and was the editor of the Eton chronicle. He was a member of the chess club, the literary society, and a bebop group. He was part of the drama club, playing Antony in the school's performance of Antony and Cleopatra. He was social and cheerful.

After Eton and before starting at Oxford, Parfit was offered a position with New Yorker magazine and took it, where he worked as a researcher for the "The Talk of the Town" feature column. Once at Oxford, Parfit opted to study history instead of philosophy. Clearly, he was not yet convinced that life’s biggest questions were in meta-ethics. (Oddly, Parfit never actually received a formal degree in philosophy, resulting in some criticizing him for a lack of philosophical depth later in his career.) Overall, Parfit's early life was marked by a surprising engagement with areas outside of philosophy. As Edmonds writes, "Those who knew him only as a narrowly and feverishly focused adult would be startled by the range of his interests [in his youth]".

One thing was clear from Parfit's early days: he was brilliant. He was consistently at the top of the class at the Dragon School (a prep school for pre-teens), winning the top scholarship to study at Eton. Then, at Eton, Parfit "collected an almost embarrassing array of prizes in his final year: the chess prize, the essay prize, the Latin prose prize, an art prize, the school prize for French, the reading prize, the English literature prize, and the overall Gold Medal prize." All in all he won sixteen awards while there, an unprecedented number according to Eton's archivist. He proceeded to be awarded the Brackenbury, Balliol college's top scholarship to study at Oxford.

At Oxford, Parfit won the HWC Davis Prize for the university's best performing history candidate, and the Gibbs Prize for the highest average mark on a set of history essays. Writing in support of his application to Oxford, his history teacher at Eton said "I can say, unhesitatingly, that Mr Parfit is the best historian I have come across in my fourteen years’ teaching experience." After Oxford, Parfit applied for a Harkness fellowship, the American equivalent of the Rhodes Scholarship. In support of his application, his Oxford tutor described him as "exceptionally gifted", "the ablest pupil I have ever had," and "an absolutely first rate man, brilliant, charming and yet disarmingly modest." Unsurprisingly for anyone, he was awarded the fellowship, which allowed him to spend two years at universities in the US.

Multiple US universities fought to have him visit. In the end, he decided to spend most of his time at NYU and Harvard. Edmonds hints that it was during this time in the US that Parfit fell in love with philosophy and decided to dedicate his life to it. He arrived in the US wanting to learn more about various subjects, including sociology, psychology, and philosophy. But he emerged from his two years in the US hooked on philosophy and, encouraged by some of the best philosophers in America, returned to Oxford to pursue a BPhil—a two year philosophy degree.

This was in 1967 and, unbeknownst to Parfit at that time, marked the beginning of his lifelong journey as an Oxford academic. He won an All Souls fellowship—widely considered Oxford's most prestigious fellowship—at the beginning of his BPhil, granting him seven years of fully-funded time to pursue his own research with no other obligations. After those seven years he won an All Souls Junior Research fellowship which gave him another seven years of freedom. At some point along the way Parfit's degree status was lost, and he became the equivalent of a full professor without ever receiving anything higher than an undergraduate degree.

It was during his time at All Souls that his personality began to change. He became a recluse, valuing only time he spent working on philosophy. He became "intensely uncomfortable in the normal social world," and avoided social events unless they were work-related. When an ex-student invited him to his wedding, he "wrote a nice note to say he couldn’t come because, firstly, at these occasions there was no time to have meaningful conversations and, secondly, that he had to maximize his work time."

While most of his old friends found it in their hearts to forgive his quirks, his antics made him increasingly difficult to put up with.

His social awkwardness grew more debilitating. If there was a dinner after an event, he would fret about seating arrangements and whom he would have to converse with. A friend from his undergraduate days, Deirdre Wilson, who knew him sufficiently well to have spent a few weeks living at 5 Northmoor Road after her Finals, found herself sitting next to him at an All Souls dinner. She had been looking forward to reminiscing about the past and reminded him of their old friendship. ‘He said, “I don’t talk about the past,” and he turned away and didn’t address another word to me for the rest of the evening.’

As his obsession was deepening, Parfit found small talk increasingly difficult. When faced with a new conversation he had two signature openings: What are you working on, and what are you thinking of as the title of your book? When non-philosophers were elected as Prize Fellows at All Souls, Parfit would suggest they abandon their discipline and take up philosophy because he felt it was more important.

Somewhat astonishingly, Parfit did get married. His courtship of the philosopher Janet Radcliffe Richards was “protracted and decidedly strange.” It began with a screening process: he read her book, The Skeptical Feminist, to judge the quality of her arguments. She passed. But it’s hard to say the relationship was a happy one. Philosophy remained Parfit’s primary, if not only, interest:

Derek and Janet were together for over three decades, but Janet is clear-eyed about her position in the hierarchy: ‘I was a side show in his life. The real show was philosophy.’ She also wrote, ‘I can’t think of anything we did together that wasn’t what he wanted to do.’ All the concessions in the relationship were made by her.

They were together for three decades before deciding to get married. This was Janet’s idea, and was mostly for pragmatic reasons. Parfit didn’t invite anyone and there was no honeymoon because he was working; it was “out of the question.” In On What Matters, his magnum opus, Parfit acknowledges hundreds of people for help with the book. Janet’s name is absent.

It was not only his social attitudes that changed while he was at All Souls, it was also his work style. The early Parfit longed for passionate disagreement and debate. But the later Parfit stopped listening to opposing views. He became rigid and dogmatic:

It happened gradually, but, as a philosophical interlocutor, Parfit slowly ceased to be a receptive listener who would give a sympathetic hearing to an opposing position. The gymnastic imagination, with its shape-shifting flexibility, receded. Its place was taken by a more rigid mind. This was manifest in the narrowing of his interests. There had been a time when he would become engaged with a myriad of philosophical questions that his colleagues were grappling with. Now he was only interested in the few issues that mattered to him. Almost everything he did became an extension of his own project.

What was the cause of Parfit's descent into intense monomania? Edmonds discusses several possibilities. Perhaps it was the pressure he faced at All Souls when trying to get promoted. This forced him to complete his first book, Reasons and Persons, on a deadline, resulting in two years of intense work. Or perhaps he had always been like this, but had hidden his real personality from the world until he received a Senior Research Fellowship in 1984, securing a position at All Souls for life. Maybe this allowed him to finally give in to his authentic self. Or perhaps Parfit was autistic, a diagnosis Edmonds had believed when he started writing the book, but later disavowed.

Or perhaps it was the work itself. Parfit became focused on "unifying ethics"—showing morality is real and objective, and that the major philosophical theories of deontology, consequentialism, and contractualism are in fact one and the same once their kinks are ironed out. Parfit thus came to focus more and more on “meta-ethics”—the study of the foundations and nature of morality—instead of practical ethics or any other area that used to interest him, such as personal identity or population growth.

He spent the last twenty-five years of his life anguished by philosophical disagreements he had with other philosophers. In particular, he grew increasingly upset that many serious philosophers believed that there was no objective basis for morality. He felt that he had to demonstrate that secular morality— morality without God— was objective, and that it had rational foundations. Just as there were facts about animals and flowers, stones and waterfalls, books and laptops, so there were facts about morality.

He genuinely believed that if he failed to show this, his existence would have been futile. And not just his existence. If morality was not objective, all our lives were meaningless. The need to refute this, the need to save morality, was a heavy emotional as well as an intellectual burden. How he came to bear this burden, and how it shaped him from being a precocious and out going history student into a monastically inclined philosopher obsessed with solving the toughest moral ques-tions, is the subject of this book.

Whichever hypothesis you prefer, it's hard not to read Parfit as a tragedy. It's the story of a brilliant young man who could have used his astonishing mind to tackle any number of important questions but instead became lost, both personally and intellectually, in the miasma of meta-ethics. Many moral philosophers will shudder at this description, attributing to Parfit some sort of God-like status in their field. Indeed, Edmonds himself compares Parfit to other philosophical giants such as Immanuel Kant.

I think such comparisons are misguided, and are often inspired more by Parfit’s legendary personality than by a sober reflection of his life’s work. I think we can conclusively say that Parfit's project failed. His final tome, On What Matters, running more than 1,900 pages, is rarely mentioned by anyone, let alone read. Has it solved ethics? Do people treat consequentialism and deontology as the same moral theory? Not even close.

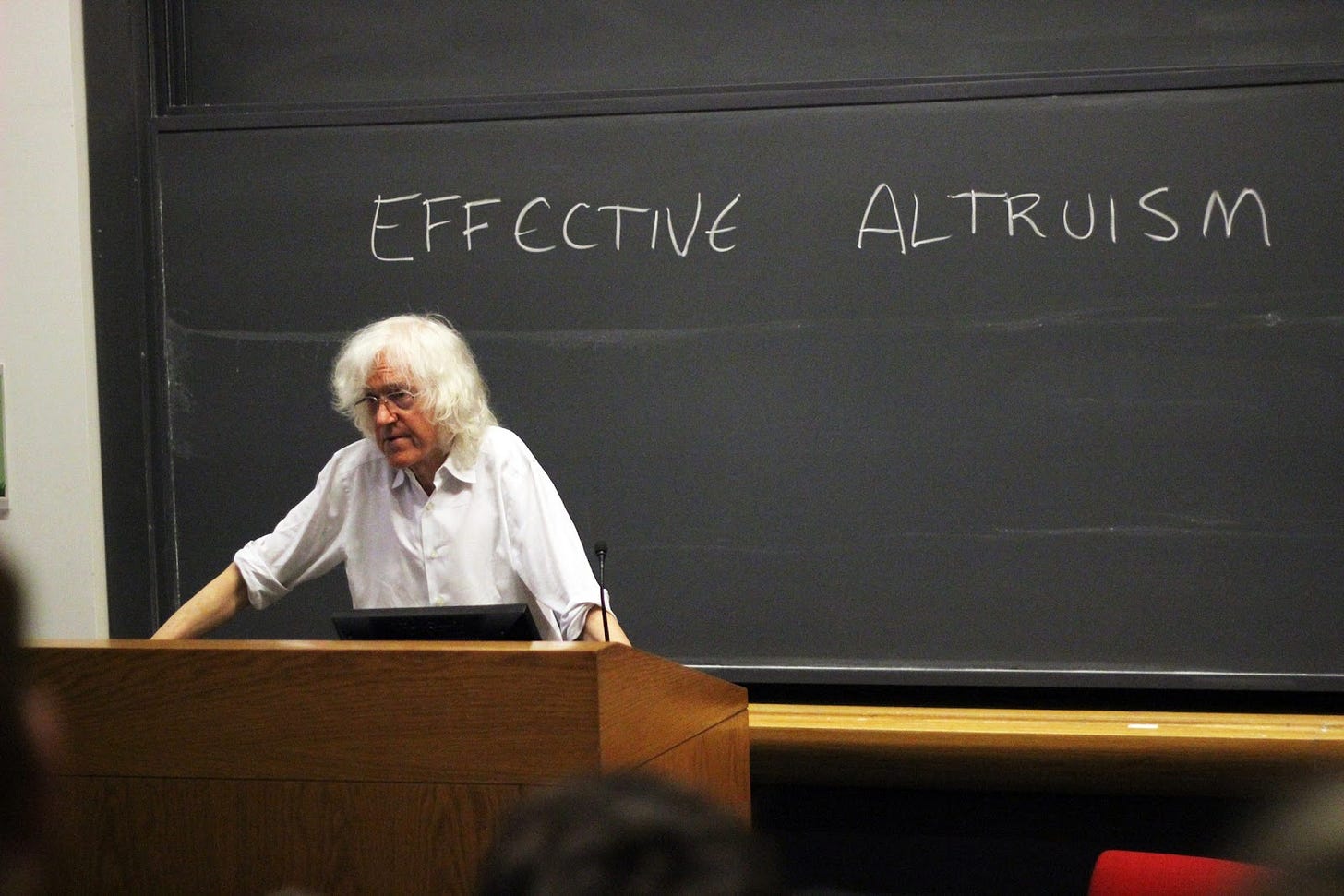

Those searching for the impact of Parfit’s work will often locate it in the Effective Altruism movement. But beyond a general encouragement to do the most good possible, it’s hard to say precisely what this influence was. Edmonds, for one, thinks that Parfit encouraged the movement to “swivel its orientation to the long term, rather than focusing solely on the present.” This would make Parfit one of the grandfathers of longtermism which, admittedly, I don’t find to be particularly admirable.

But even if you think the focus on longtermism is a good thing, Parfit’s support of such ideas came about as a result of his views on population ethics, which was work done earlier in his career. In fact, Parfit’s influence was nearly inversely correlated with his focus on meta-ethics and his embrace of social seclusion.

Parfit’s first book, Reasons and Persons, is the more influential of his two major works (17,000 citations compared with 3,000). And it was written on the basis of ideas he had at the beginning of his career. Perhaps his most well-known work overall is on the nature of personal identity, which is the first philosophy paper he ever wrote. In other words, as Parfit became ever more obsessed with philosophy and cut himself off from the world, both he and his philosophy suffered.

Was his sacrifice worth it? At the end of his career, All Souls threw him a retirement party and told him he could invite friends. He didn’t invite anyone because, as he told Janet, ‘I don’t really have any friends.’ It seems clear that, in the end, Parfit did not figure out what mattered.

Thanks to Philippe-Antoine Hoyeck for catching a typo in Parfit’s book title, and to Royal Quaye for correcting “New York magazine” to “New Yorker magazine.”

I think we have to separate Parfit the person and Parfit the philosopher. Parfit the person does seem like a tragedy of the sort you only find in the narratives tortured artists self-perpetuate. But in his case it seemed to be genuinely motivated. Certainly not a life I want to live but also not a life wasted *if his work was truly great*.

It's on that point that I feel like a crazy person. You're absolutely right to point out that seemingly no one has read it. I've asked at least a dozen moral philosophers, professors, grad students, hobbyists, and I've met exactly 0 people who have read it. So it was incredibly surprising to find that when I finally got around to reading On What Matters (I'm wrapping up volume 1 this month), I was shocked to find that it's, well, incredibly good.

I've gone through all the big names: Scanlon, Korsgaard, Foot, Railton, Lazari-Radek, Singer, etc. and I would say that Parfit is leagues ahead of them in both precision, clarity, force of argument, and cogent ideas. I would even go as far as to say he's the best Kantian I've read, and I say this as a Korsgaard fan.

I think he gets the core right: reasons are the fundamental unit of account in normative thinking. Reflective equilibrium is the best methodology we have to uncover anything approximating moral truths. It's intuitionism, but intuitionism is the best we can do. And Parfit, over the course of countless pages, considers principle after principle, subjecting it to various unusually not-outlandish thought experiments, and shows which principles stand the relentless scrutiny. On What Matter's Parfit is best described as a tactician who, with 25 years worth of patience, ends up inching his way towards the land grabs of a masterful tactician.

The real failure in Parfit's work, it seems to me, is his failure to be more concise. Because the quality is most certainly there. It's even significantly clearer than Reason and Persons which I found at times unnecessarily hard to follow. Perhaps it's not as mind bending as Reasons and Persons, but the arguments are just as sharp and for something with significantly higher stakes. It seems to me that given the typical load of an academic's work schedule, it's simply infeasible to read 2000 pages of analytic philosophy. But as a hobbyist with time on his hands, I can and in my estimation thus far, he seems to have succeeded. So I don't think it's crazy to say Parfit was the greatest moral philosopher since Kant.

fascinating review. lol at people looking down their nose at him for not having a proper philosophy degree!

I'd be curious to hear more about why you consider meta-ethics a waste of time. Afaik a big chunk of his second book is defending objective moral realism, which seems like it could be an important project if you subscribe to the Deutsch line on this kind of thing