Book review: One hundred years of solitude

Incest, flying carpets, and ice, all fractally wrapped into a bundle of mega pessimism.

This is one from book club. You can listen to the episode here.

Like a set of Russian dolls, Gabriel García Márquez's One Hundred Years of Solitude consists of nested storylines all following the same pattern:

(a) Innocence and curiosity leads to (b) aspiration or modernization which leads to (c) a fall of grace or corruption which ends in (d) failure, decay, and erasure.

The first doll is the town Macondo itself, founded as a utopian, isolated village where "no one ever died." But the town can't help but modernize, first by trading with gypsies who bring new technology and then by becoming the manufacturing center of the Banana company. This interaction with the outside world ends in the "banana massacre," in which thousands of villagers are slaughtered by the company's hired mercenaries. The government erases evidence of the massacre and eventually the town of Macondo itself disappears.

Next there is the Buendia family line, which begins with the marriage of José Arcadio Buendia and Ursula—the founders of Macondo. Their descendants engage in politics, commerce, and science but all fail in time, and the family eventually folds in on itself via violence and incest. The last child in the family is born with a pig's tail, symbolizing their ultimate decline. Everyone in the family is eventually lost to history.

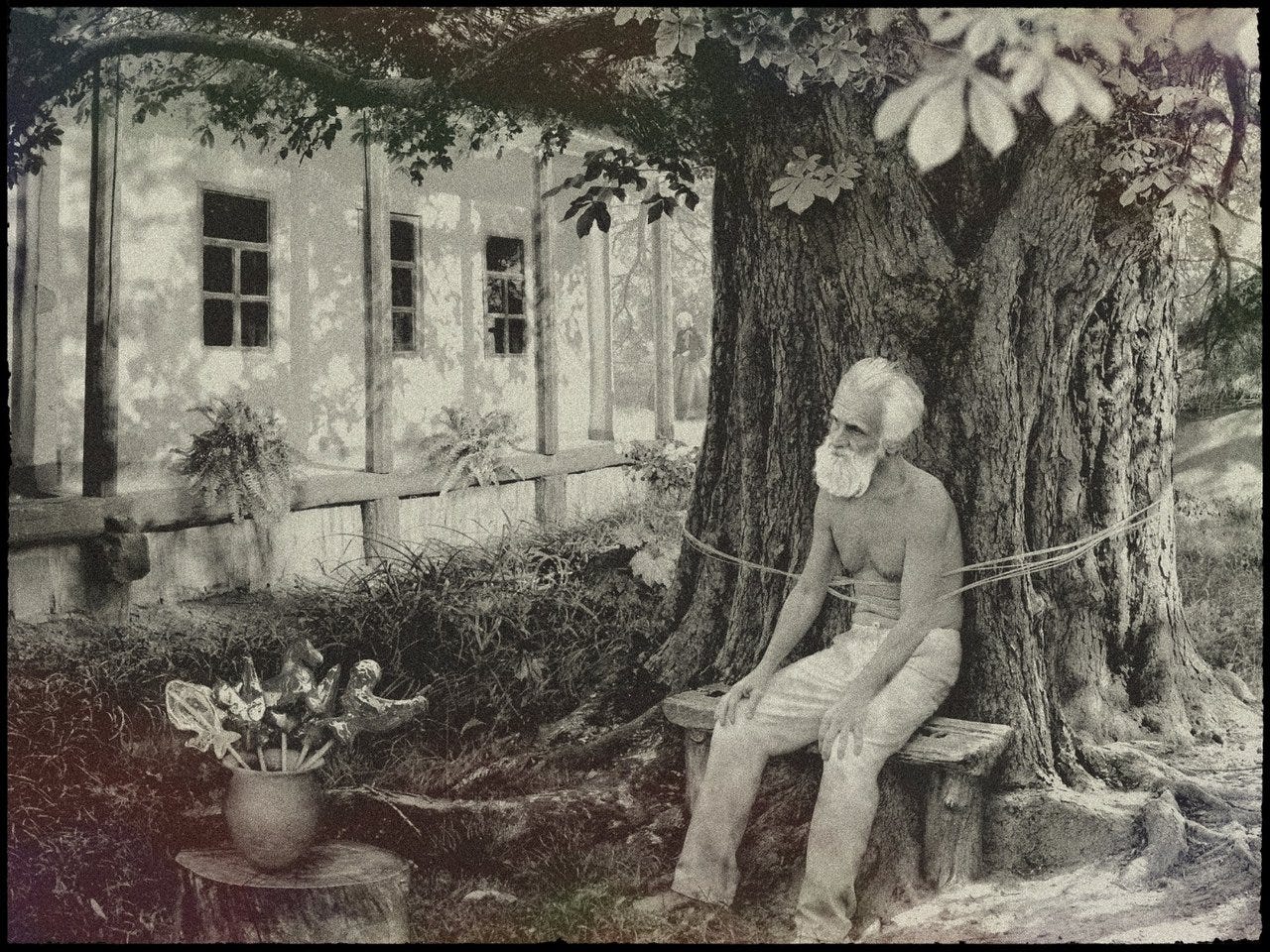

Then there are the arcs of the individual characters, all marked by tragedy. Inspired by the gypsy Melquíades, José Arcadio Buendia becomes curious about science and develops a fascination with magnets and ice. But his thirst for knowledge becomes obsessive and he abandons his family and his responsibilities. He goes mad, and ends up tied to a tree for many years until he dies.

The colonel Aureliano Buendia, José Arcadio Buendia's son, pursues alchemy alongside his father as he's growing up. Like many young men, he's eventually seduced by a politically righteous cause which results in him joining a civil war. The 32 battles he fights (all of which he loses) see him transformed into a sadistic and cruel general. Embittered, he nearly orders the execution of his friend and then shoots himself in the chest. But even that fails. He lives out the rest of his life sad and lonely.

José Arcadio, José Arcadio Buendia's elder son, is well-intentioned as a young man and leaves Macondo on an adventure. He returns as tattooed and decadent, throwing orgies. (One cannot help but think of Judge Holden in Blood Meridian.) He is eventually murdered.

Amaranta’s childhood is full of love and potential. She courts Pietro Crespi but ends up rejecting his love and succumbs to bitterness. She deliberately chooses to sabotage her own chance at happiness, engaging in a pseudo-incestuous relationship with Aureliano José, and eventually dies in isolation.

One can keep going. Pilar repeatedly falls in love with different members of the Buendia family but each relationship withers and dies. Gaston attempts to bring aviation to Macondo but ultimately abandons the project. Renata finds joy in music but, because of her mother's violence, eventually withdraws into a lonely life of silence.

Finally, the arc appears in various little subplots. The colonel learns to craft little metal goldfish as a boy, but this activity later becomes compulsive and meaningless as he melts them all down to make more. An attempt by Visitacíon to escape war leads to the insomnia plague and the town's collective loss of memory. Remedios' beauty corrupts the hearts of men and leads to infighting. The railroad is an initial attempt to connect with the outside world, but gets abandoned after the banana massacre.

Given the appearance of this pessimistic pattern at every level of analysis, it's hard not to read the book as a commentary on the futility of aspiration. Any sort of novelty ends in disaster. We are treated to never ending cycles of hope and agency stifled either by the whims of the world or the flaws of the characters themselves. There are no silver linings. The lesson—represented by Melquíades' parchments which hold the prophecy of the destruction of Macondo—seems to be that we're destined for a miserable decline.

As a Rosling-Pinker-Deutsch pilled optimist who thinks that the world has gotten, and can continue to get, a lot better, this thesis is hard for me to swallow. And even though your enjoyment of fiction should not depend on agreeing with the author's politics, it was hard for the pessimistic themes to not affect my reading.

That said, given this thesis, I can appreciate some of the stylistic choices Marquez made. The book is hard to read—not because of the vocabulary or the DFW-style page-long sentences, but because everything is blurred together. You jump from one event to the next, one character to another, one generation to its successor, too quickly to track. Pages and chapters bleed together; page 100 feels the same as page 300.

It doesn't help that nearly all male Buendia family members have one of two names: José Arcadio or Aureliano. This is on purpose—the point isn't the difference between the characters, it's their similarities. Regardless of the specific details of their life, we're meant to notice that whatever they try ends in tragedy. The reader who gets caught up in mapping out each character, figuring out exactly who is related to who and who is sleeping with who and who has which hobbies and which vices is missing the point.

The magical realism deployed by Marquez serves a similar purpose. With it, he can introduce disasters freed from the constraints of a realistic physics. José Arcadio Buendia can be tied to a tree for dozens of years; the entire town can go without sleep for weeks; it can rain for four years and eleven months; Remedios the beauty can literally ascend to heaven; José Arcadio's blood can weave through town to his mother's house; Melquíades' parchments can foretell the history of Macondo down to every detail.

That is, Márquez uses magical realism to highlight and heighten the corruption and decay phase of our arc. It allows him to make the erasure of various characters, and eventually Macondo itself, more devastating and symbolic than reality would allow.

But after reading 400 pages of magical realism, I'm of the firm opinion that it should be a device used very sparingly by authors. The cudgel it becomes under the pen of Marquez leaves the reader exhausted—you stop having expectations about the book because anything could happen. And, as Rich points out in the episode, it limits your ability to empathize with the characters, because you don't know what kinds of solutions are available to them to solve their problems. Maybe they can use flying carpets like Aureliano, or use a magic mirror like Melquíades, or have a self-playing piano like Pietro.

Somebody should have introduced Gabriel García Márquez to Jorge Luis Borges. Borges was also a master of magical realism, but had the instinct to never stretch it across an entire novel. He knew that it was best dealt in smaller chunks. One Hundred Years of Solitude could have been condensed into a short story without losing much. If you write a book with the lesson that the details don't matter much, then adding 300 pages of unnecessary detail seems a bit aggressive.

If you're going to read Márquez's magnum opus, read the first 100 pages, understand the tone of the book, and then put it down.

You can watch our beautiful faces discuss the book if you haven’t had enough of my complaining:

Wow this is tough to read … but I have to challenge this perspective … to me he was trying to show what happens when people forget their past, repeat the same patterns, and become trapped in myth instead of meaning. There’s something deeply human and soft in the way Márquez writes about failure. The tragedy isn’t that everyone is destined to failure. It’s that they almost remember, almost change, almost break free. That yearning is the emotional core of the book. Not cynicism but the reminder of what could’ve been. I take it as a challenge to live a better life…

You have to be more invested in Latin American history to understand the pessimistic tone of Garcia’s writing. You have understand the revolutionary/reform-stagnation cycles of the region, otherwise you’re not going to understand it at all.

Also disagree on the book being a hard read or hard to follow, maybe if it’s a lapsed reading. The book’s narration clearly differentiates between members of the Buendía family by employing titles, full names, and middle names. IIRC most modern editions come with a family tree.